At Pedaal, we’re experts in Cyclelogistics. Not a term you’ve heard before? Cyclelogistics is performing commercial deliveries by cargo bike! And, there’s real simplicity to the concept too. A cargo bike is faster than a truck in urban gridlock. A cargo bike is cheaper than a truck. And, it turns out, a cargo bike can deliver more than a truck too. (We’ll talk more about that below). But what seems simple on paper grows more complex in reality. And, nowhere is this more clear than in Toronto; a city that leads the charge in North American cyclelogistics. That’s why it was great to host Martin Seissler, an expert in cyclelogistics, who runs a cargo bike consultancy called CargoBikeJetz in Berlin. While it was very clear that Canada is still trailing Germany, the answer to this might very well be the trailer… Read on!

Bikes are Faster

Martin began his presentation by talking about how cargo bikes can unlock the main problem; and that’s gridlocked traffic. The problem with gridlock is just how unnecessary it actually is. Gridlock is not unlike an addiction that we all hate but we all continue to afford. Studies have shown that in the United States, 52% of all urban car trips are just under 3 miles, a distance that is always faster by bike – and certainly more affordable. As a recent Forbes article states, this reality has been proven anecdotally hundreds of times by staging “commuter races” that prove a bike is faster. (Our favourite is the Top Gear episode where a boat, bicycle, car and subway compete for the fastest time. Spoiler alert: the bike wins)

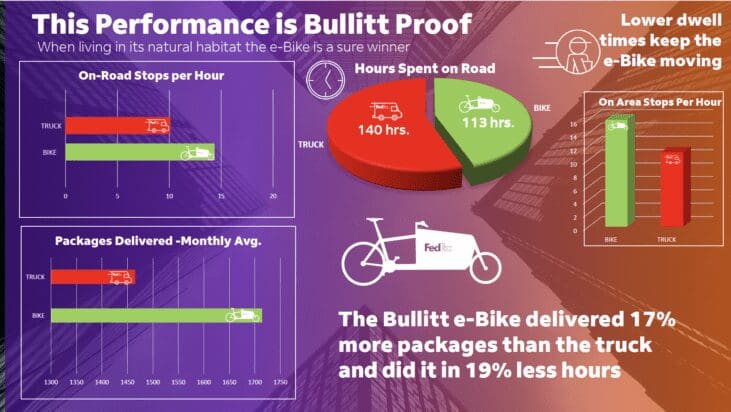

But the real mathematical data that proves bikes are faster is not anecdotal. It has been measured and delivered by freight companies. On the start-up side, global companies like Uber and Deliveroo have used bicycles as a profitable disruptor, proving that their bikes are always faster than using a car. At the same time, more conservative and established courier companies are listening. From 2019 to 2022, Eric Kamphof – one of the owners of Pedaal – sold over 100 Bullitt bikes to FedEx after their initial pilot proved that a cargo bike could outperform a van. These bikes – operated from Miami to Halifax, and from to Toronto to Vancouver – continued to show that cyclelogistics is the winner. A cargo bike delivered 17% more packages than a truck and did it in 19% less hours. You can read the complete FedEx report here.

Cost of the “Last Mile”

If delivery companies are taking cyclelogistics seriously, we might want to listen to them. After all, consider each road as a kind of accounting balance sheet. For commuters driving to work, the road is an expense; no one gets paid to sit in traffic on their way to work. But, for a freight company, a road is how they make money. So, the question both a commuter and delivery company have to ask is: what can I afford? For a commuter driving under three miles to work, they’ve chosen to afford the gridlock. In fact, they’re really the ones creating the gridlock. But, for a delivery company, they cannot afford it. Expenses like trucks and wages can only monetize if traffic is moving.

According to delivery companies, the cost of the “last mile” on a package delivery is mammoth. A package could go from side of the country to the other,but 51% of that packages cost will incur in the final stage – or “last mile” of delivery. The problem is that e-commerce deliveries are project to increase at a rate of 10% a year which does not factor the 30% increase forecasted for Toronto’s population by the year 2030. So, if there are already too many short-distance drivers congesting streets, now add 10% more delivery vans. Now add even more cars. It’s shameful that a city like Toronto has the third worst gridlock in the world. And, the cost of lost economic opportunities in Ontario is projected at an estimated $50 billion dollars per year. The question really is: can our cities afford this?

Microhubs are necessary

But, cargo bikes don’t provide the complete answer. Neither does a truck. As Martin showed, this is where delivery companies are experiencing some minor growing pains. Successful cyclelogistics is a matter of real estate. Currently, a long-distance tractor-trailer will deliver goods to a large centralized consolidation depot. This depot sorts the packages and places them into smaller vans. These vans then deliver to a long list of downtown addresses, and along the way – this is the problem of the “last mile” – these vans get immobilized in traffic. It’s as easy to see a FedEx van stuck in traffic as it’s easy to imagine how a cargo bike can’t ride all the way to a suburban feeder depot to pick up and deliver a load.

In short, the centralized consolidation depot remains necessary, as are the smaller vans that can negotiate downtown streets far better than long-distance tractor-trailers. But, what is equally necessary is another piece of real estate – and here also many companies have been quite creative. This piece of real estate is called a “micro-hub” or a feeder-hub in the logistics business. If you’re in Toronto, there’s a good example of a Purolator microhub at the University of Toronto campus. A microhub is the perfect in-between; it serves the capacity of the van delivering from the central feeder hub, and also serves the fleet of cargo bikes that deliver goods more efficiently in downtown cores. Since an electric cargo bike is proven to be faster than a car in distances up to 10km (see this study for more info), microhubs tend to be spaced 5km or more apart.

Microhubs are an investment

Why do delivery companies have to be creative with micro-hubs? As Martin demonstrated, the answer is obvious. While micro-hubs are small, they are also located in downtown real estate where property value is high. This is why, for instance, public-private partnerships like the Purolator hub have been successful, as has the Colibri project in Montreal; which uses a dormant Greyhound bus station. Companies like Amazon have been remarkably creative, using a moving (or parked) box truck to receive and transfer deliveries. Companies like FedEx have been quick to jump on cargo bikes but hesitant to commit to the higher-investment real-estate piece. Smaller start-ups like Toronto’s NRBI, who handle a bulk of the downtown Amazon shipments, don’t need anything quite so big as the Purolator hub and are also repaying capital costs (FedEx bikes were bought by a leasing company, NRBI paid cash on demand).

But, what if you can’t afford a micro-hub? Then what? This is where our conversation headed as our cyclelogistics industry night turned into a long, spirited discussion (We left at 12am!). As it turns out, the same question is very much occurring in Germany as well. Part of this is the relative newness of “cyclelogistics”; companies appear to be relying on the cargo bike for their metrics as a “wait and see approach,” although the consensus appears to be that all are quite thrilled with the bottom-line results. The challenge during this period is to find a future-proofed solution that works where microhubs are still being assessed, but are ultimately convertible to micro-hubs once microhubs become critical infrastructure. And, the solution can be found in Belgium.

Watch the Trailer

In 2023, Bullitt Cargo bikes collaborated with Brussel’s Urbike and data analysis company Kale AI. Bullitt and Kale AI affixed GPS units to each Bullitt bike in Urbikes fleet. While many companies had produced their own data around cargo bikes, what was missing was a rigorous methodology that helped determine what tool worked best where. Like vans, cargo bikes come in all shapes and sizes. And, sometimes a van will work better than a cargo bike. But which tool, when? Where? The point was to create a time elapsed dataset that was fundamentally spatial in scope. If you’re into this topic, be sure to read the complete report here.

But, what made the Urbike project interesting is that Urbike also struggled with microhubs. As a co-op, they didn’t have the cash to purchase or rent lots of land throughout Brussels. They needed something that could double or even triple volume without any compromise to speed. The solution also had to be low maintenance. The choice was a Fleximodal trailer. The Fleximodal trailer is a highly modular system that can switch between pallets, freight boxes, and customized boxes.

Besides this modularity, the Fleximodal trailer can also be detached from the bike. This means it can operate as a trolley or it can be stored at the depot while the cargo bike manages a route with less volume. At only 89cm wide the trailer will not get stuck in traffic. And, best of all, it is designed to track the bike perfectly in high-speed corners. Plus, with 1200L of space plus another 400L upfront with the Bullitt-X bike, there is a 300% increase in volume. Best of all, its low tech and quick to fix.

Bikes for riders, not CEO’s

What Urbike did not do is buy a larger three-wheeled cargo bike as FedEx did in Montreal and Toronto. As bike people, we like to joke that there are delivery bikes designed for delivery company CEO’s and delivery bikes designed for riders. The bikes designed for CEO’s tend to look an awful lot like trucks, and because they are often one meter wide or wider – a Bullitt is only 44cm wide – they get stuck in traffic the exact same way a van does. But, the biggest problem with these “bikes for CEOs,” however, is the wide array of complex non-standard parts, whether they are proprietary or borrowed from the motorcycle industry. The longer it takes for a mechanic to fix the longer that bike isn’t delivering packages. As Martin noted, it also doesn’t help that these bikes-that-look-like-trucks seem to keep going out of business.

Mistakes will be made on the way to progress. What’s important is that cyclelogistics is proven to solve a global problem, and that requires a global conversation. To host cargo bike owners and operators alongside academics, urban planners and the City of Toronto all in one room was already an important conversation missing. To have this conversation led by a global expert was intoxicating (plus, we did serve beer). With such a successful evening under our belts, we hope to invite even more special guests who can speak to this topic, and help this solution grow. Thanks to Martin and especially thanks to my parents (they’re the white haired people in the back) who took pictures!