Brompton is an astonishing company. That they exist is a tribute to stubbornness. We can say this as their stubborn Canadian counterpart. In 2006 – while we were the managers of another bike retailer – we first imported Brompton into Canada. This path led to Pedaal today. But, our success will always be tied to Brompton’s success. That’s because Brompton is a company who makes things work. To the level of astonishment! Of course, Brompton’s success will always be tied to its retailers and those who ride a Brompton. Let us share our Brompton Bicycle history in the hope that it can be a footnote to your own!

Sliding Doors

Back in 2006 the owners of Pedaal were running another bike store owned by a real character. This is important, because Andrew Ritchie, the founder of Brompton, is also a real character. We’ll always remember a visit to the Brompton UK factory in 2014, where Andrew – already in his 70’s – turned around in his office chair to say hello, ask us how things were in Canada, and then went right back to his computer. We can only imagine he was still plugging away at some infinitesimal improvement. But, that’s the Brompton story: perpetual inch-by-inch improvement that, in some banner years, came together as epochal.

It was in 2008 that Will Butler-Adams (above, left) was appointed the CEO of Brompton by Andrew Ritchie (above, right) and we bonded with Will several times over stories about our respective founders. In many ways, we were in the same boat. Will had met Andrew Ritchie through a real “Sliding Doors Moment,” after a random meeting with a close friend of Andrew Ritchies on the same city bus. Pedaal’s Eric had also gotten his job also through a friend, and in just two weeks of work, was suddenly running the show. Like Will, we were all square pegs that didn’t fit into round holes. Will was told he was stupid in high school; both of us at Pedaal were told the same.

But, doing stupid things can sometimes work, as the Brompton Bicycle history shows. Over several trips and several pints in London, we could all smell the opportunity. For Will Butler-Adams, a Brompton bicycle was an established sight in London, but it hadn’t reached its tipping point or true potential. It was a bit… professorial. Eccentric. Not quite cool yet. For us, selling Brompton’s was a way we get people out of cars and into urban cycling all the while internally challenging the culture of a very masculine, suburban, and athletic-oriented industry.

Square Pegs

Will Butler-Adams has always been quite transparent about his old boss, whether in interviews or with us at the local pub. He’s called him a “constructive pain in the arse,” “cantankerous and eccentric,” and noted that on good days “…I’m sure he has respect for me.” We remember Will telling us that Andrew – who called himself a “thoroughly unmarriable chap” – still lived in the same 500 square foot apartment he moved into when he was in his twenties. How in the early days, Andrew’s apartment was filled with prototype Brompton frames and automatic watering devices (to cover the bills he was a landscaper for years). A lot of this lore has been recounted Will’s fantastic book.

Our boss was also a real character. However unlike Andrew, he rarely showed up for work. He was the consummate starter of things, but once going, a very poor manager. And, he knew it too; that’s why he employed people like ourselves to run things. He trusted us, but in a more important way, he trusted our ideas and supported them enthusiastically. Sadly, he is no longer with us. And, it became clear that the company had other priorities with his passing. That’s why we started Pedaal, to be a Canadian leader for Brompton Bikes and keep that bright vision burning.

Bollo Lane

Quirky founders and tight partnerships are a great way to start a story, but where does it go from here? We might begin with astonishment. This was certainly Will Butler-Adams own position as he took us on a tour of “Bollo Lane,” the old Brentford factory back in 2008. Will had only recently taken control and began our tour with a single sentence, “1,200 proprietary parts, I want you to remember this: 1,200 proprietary parts.” Indeed, as we walked through the cramped Brentford factory, we could see that a Brompton wasn’t just a frame made in the UK. Nearly all of its proprietary parts were made in the UK. And, there were 1,200 of them! Mercy!

Will’s own astonishment can be found in a 2010 interview with Fast Company: “It was all 1930s, no machinery, all done by hand, and very old-school… I was like, ‘Blummin’ Norah, this is amazing!’” We felt the same, minus the British idiom (who, exactly is Norah?). In a world that was moving swiftly to just-in-time logistics, pioneered by Toyota and Dell Computer, here was a company that was going the exact opposite direction. And, the thing was, it was working.

Re-tooling the Industrial Revolution

This production method, called “vertical integration” was a throwback to the Industrial Revolution, when everything was made in house. Even Raleigh, whose vast Nottingham factory was once famous for having raw materials like rubber and steel enter at one end and a bicycle at the other, had moved everything offshore. But, the crazy part of tour was the Brompton tooling shop where the tools to make these parts are made. As Will states about the tooling, “‘There’s more cleverness in the machines than there is in the bike itself.” In fact, during our visit, Brompton had just taken arrival of a new Haas QuikCube – a $1M out-of-the-box auto-brazing tool that Brompton felt the need to re-tool. How can a company like this exist?

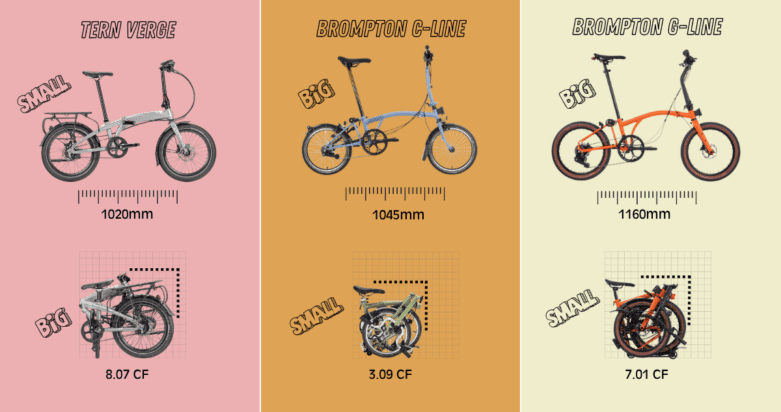

The reason that all of this exists is because Brompton produce a folding bike that actually works. (Check out our Brompton’s here). This helps explain why Brompton remains so singular. It’s a bike that is nearly impossible to copy unless you have the same company culture. On a Dahon or Tern, only the frame is proprietary – the parts are all standard. This helps explains why a Dahon or Tern don’t work all that well. Without the same engineering tolerances, both fold-up to a ghastly and un-carryable size as well as a horribly twitchy ride quality due to the short wheelbase. To copy a Brompton, you’d have to reverse engineer the frame and all 1,200 proprietary parts. You’d have to reverse engineer the entire Brompton Bicycle History!

As Will Butler-Adams states in this article:

Most manufacturers will design a bicycle around, say, Shimano’s range of gears and braking systems. This standardisation creates more flexibility when it comes to where (and how) the bicycle is manufactured. However, the evolution of the Brompton has resulted in a bike where nothing is standard. Brake levers, tires, rims, hub gears, derailleurs, chain tensioners and cranks are all designed and developed in-house. In effect, Brompton is an engineering company that happens to make bicycles.

“Just in Time” for Disruptions

Truth is, the batch production that cramped production lines was not sustainable. As Will Butler States, Old Bollo was “…was gradually strangling us.” As we walked through Old Bollo, we asked Will why certain non-essential parts couldn’t be made by other suppliers and delivered in a “just in time” manner. Already in 2008, and just new at the helm, Will confessed that this was his plan. Certain “non-core” parts would be subcontracted to outside vendors. This strategy became part of the “huge gamble” to move to the new Greenford facility.

While clever on paper, this idea couldn’t weather the massive geo-political disruptions that were to follow. Worried about the effects of a hard Brexit, Will Butler-Adams stored $1M pounds worth of spare parts. Covid was another reason to stockpile parts. Even more complex was the launch of titanium-frame parts in 2006. The Russian invasion of Crimea and subsequent invasion of Ukraine left them without a titanium source. This has led to more prescience and care over supply chains. For instance, Brompton has recently pulled its purchasing out of Taiwan in fear that Taiwan and China might go to war.

In a market where most products are produced “just in time,” many of Brompton’s parts continue to be produced in the same UK factory. While each of these supply chains have their own sources of disruption, most companies will choose to deal with one source of friction – not two. But, not Brompton. Nope. They make it even more complicated with a third kind of supply chain: one that goes beyond mass-production and recalls the British obsession with craft. (The above video is a great teaser).

Vestiges of a Medieval Guild

It’s probably not quite right to compare the vertical integration of Brompton to the Industrial Revolution. If anything, Brompton combines elements of the Industrial Revolution with the later Arts & Crafts movement which combined mass-produced scale with individual craftsmanship. Members of the Arts & Crafts movement were famous for resurrecting something of the old Medieval Guilds. Nowhere is this better seen with Brompton than their commitment to brazing frames – which Will Butler-Adams referred to as a “Dark Art” on our tour – and this curious mode of production called “mass customization.”

We’ve been to the Brompton factory five times now, and the best part is watching the frames being hand-brazed. In our most recent tour of the Brompton factory back in 2021, we were given a brazing lesson (above) by head brazer Abdul El Saidi, mostly as a PR stunt. But, it also taught us just how difficult this skill is. We’ve already noted that Brompton makes 1,200 parts, each of which contributes in its own way to the whole. But, these parts are mounted onto a frame that requires absolute precision in order to fold up to something small and carry-able yet unfold to a bike that is both big and sure-footed. This takes engineering. And engineering takes an ecosystem. Part medieval guild, part Industrial Revolution, and part Just in Time, the Brompton bicycle is one of modern capitalism’s strangest success stories.

Precision Dark Arts

Consider, for a moment that a Brompton bike is made up of five parts: the rear swingarm, the main frame, the front frame, the front fork, and the handlebar stem. A regular bike is made up only of two parts: the frame and a fork. The crazy part? Even though a Brompton is brazed on five separate jigs, it comes together straighter than a bike welded on a single jig. That’s absolutely bonkers! As Will Butler Adams states,

“Good quality bikes are built to wheel alignment tolerances of around +/- 2mm. But if we stuck to that we would have a pretty terrible bike because we have five different parts that have to come together so +/- 2mm would become 1cm in the finished bike. We make our bike to tolerances of +/- 0.2mm, around ten times the tolerance of a normal bike, because when you build a folding bike you need that to get a very accurate end result.”

The wild thing about brazing is the commitment to human-resources. Most bicycle factories in China will offer their employees a two-week crash course in welding. This is because bicycle factories overseas can see staff turnover as high as 80%. But, brazing requires far more time than this. Brazing uses lower temperature brass to prevent frame deformations, and requires meticulous temperature control and muscle memory. How long does it take to train a brazer at the Brompton factory? Anywhere from 6 to 24 months! At Brompton, humans are an asset, not an expense. They are the ones who make Brompton Bicycle history.

Mass Customization

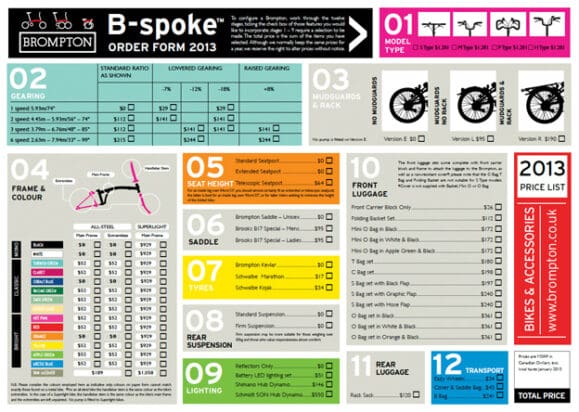

A look at Brompton’s website might allow you the sense that Brompton makes different models, all mass-produced. But, this couldn’t be further from the truth. When we order a Brompton from the UK, we do not order a model that is already stored in a warehouse. No, they take the order sheet and make the bike in a certain production week. Thus, when forecasting demand, Brompton does not ask us for the bikes we want, but how many production slots we want. We do not book bikes; we book units of time. These turn into the Brompton bikes that we carry.

While the current model range offers a number of prescient solutions engineered for different use cases, there is still a high degree of customization a customer can order – if they’re willing to wait. Essentially, all Brompton bikes are not mass produced but “mass customized.” You can walk into Pedaal and order a C-Line, for instance, with a mixed colour palette, your choice of gears, and then all sorts of other choices like rear rack, different seatpost heights, and even dynamo lighting systems. Above is the order sheet that Pier and Heather from Bromptoning used when we sold them a Brompton back in 2014. Rumour is that Brompton will bring a digital builder in 2025. We can’t wait!

In summary, Brompton hand-brazes bikes in the UK, employs a workforce that requires up to 24 months of training, designs and tools 1,200 parts, builds a large percentage of these parts in the UK, outsources others, and none of this produces a mass-produced bike, but instead a mass-customized bike. No wonder Brompton owners are a little religious about their bike. Each day, their bike comes into the office – solving the problem of theft – rides with great stability and agility on the way home, and packs up small for planes, trains and automobiles. All of this engineering produces a bike that one can get a little religious about. What’s not to believe?

Big Efforts, Effortlessly Cool

As Will Butler-Adams admits, in the early days Brompton was not viewed as a terribly cool bike. In a 2021 interview, Will stated that Brompton’s target market was “anyone who rode a bike.” But, in 2006, when we visited London, the average Brompton rider looked a bit older and… professorial: an eccentric bike for an eccentric crowd.

This began to change in 2008, partly because of the Spanish market. In most of the world, 2008 was the era of the hipster on fixed gear bicycles, yet in Spain, for whatever reason, the Brompton was the “it” bike. (The video above is amazing). In 2006, a Barcelona bike shop named Bike Tech started a funny little race called the Brompton World Championships. This race morphed to the UK in 2008, where Brompton kept their eccentric professorial cool by stating that all riders had to wear a three piece suit. It was a hot day, and we were the only Canadians in attendance (that’s us below), but we marvelled that anyone who rode a bike was there. Still unapologetically eccentric, Brompton had hit the mainstream.

Also present in the crowd was Spanish Tour De France rider Roberto Heras, chief domestique for USPS Team. (Who, incidentally, did not win). Suddenly serious riders were taking Brompton seriously. More proof of this was UK professional cyclist David Millar riding a Brompton. But Millar was also a commuter, and wanted a folding bike that took performance seriously off the bike.

“When you’re urban cycling, 90% of the time you’re off the bike. So you want to have performance for that 90%, as well as that 10% on it.”

While the Brompton was compact, it could be lighter. And while it was efficient, it could also be faster. First launched in 2018, the David Millar CHPT3 bike continues to be a sold-out success. With fast, high-pressure tires, titanium throughout the frame, and big thigh-crunching gears, Brompton even proved to stubborn bike stores that it was a bike worth carrying. But, this collaboration wasn’t the last.

Electrifying Collaborations

We couldn’t close our little tale without one last anecdote. It was on the completion of our first tour of the Old Bollo factory that Will gestured us outside and said he wanted to show us something. What he asked us to try out in the parking lot was Brompton’s first prototype of an electric bike. This bike, said Will, is “shit.” As he recounts in his book, he had been to China to check out the motor supplier and the factory was filled with men sitting on dirt floors smoking clay pipes. Even today, many of the cheaper, non-repairable, and ultimately disposable e-bikes on the market probably have the same story.

But, Will was committed to the idea of an electric bike, even if it launched nearly ten years later in 2015. A Brompton is designed to solve the congestion and health problems facing big cities. But, based on Brompton Bicycle’s history, he was also committed to doing supply chains correctly. The problem with e-bikes even today is that there are highly regulated, repairable, and quality motors offered by companies like Bosch and Shimano on one end, and absolute garbage on the other end. And, the problem with companies like Shimano and Bosch is that they don’t make motors for little folding bikes. Consider the Tern Vectron. This bike uses a Bosch motor and comes in at 48lb. No one wants to lift that.

Part of the critical use-case when buying a folding bike is the need to carry it up the stairs and into the office. It’s also nice to ride to the office on a hot muggy day using a bike that doesn’t cause you to sweat. So, Brompton – who are no strangers to doing things their own way – did things their own way. Brompton, who already worked with Haas F1 on their autobrazing QuickCube, reached out to another F1 company; Williams Advanced Engineering. Together, they produced a lightweight, fundamentally repairable and high quality motor that results in a very carry-able 27.9lb. You can check them out here.

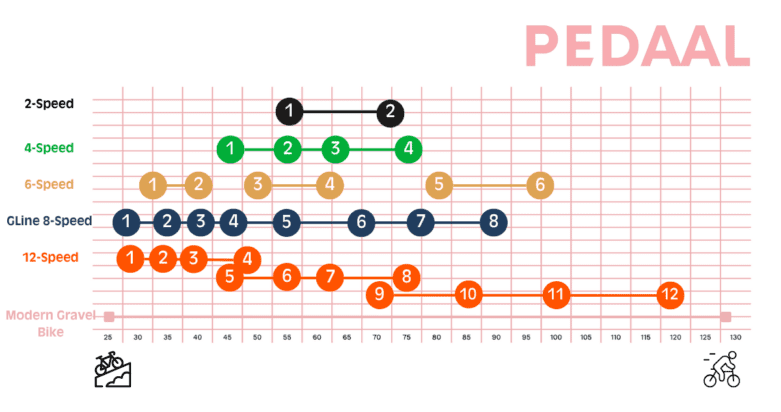

Weighted Acquisitions

The use-case of a folding bike, as mentioned, demands that it be carried. And so, the lighter the bike, the better. This, as seen, became especially true with the advent of the Brompton electric bike. By adding motors and batteries, how could the bike become even lighter? The answer was twofold. The first was to build a lighter gear system, since the internal gear hubs used on a Brompton tend to be unavoidably heavy. In 2005, an anniversary year for Brompton, all bikes feature the new Mk6 rear frame which allows for a lightweight and broadly ranged four-speed gear system.

The other way to make the bike lighter was to decrease the frame weight. This meant a hunt for lighter materials and a supply chain that could support it. Titanium is stronger than steel, about 30% lighter and has a ride quality that deliciously absorbs shock. Russia holds large reserves of Titanium and has the established industry and expertise to produce titanium tubing for cheap. But, Russia is a volatile trading partner.

In Rotherham UK, there is also a robust titanium industry. Rotherham is home to Rolls Royce engines, Stanley knives and McLaren supercars. And, in the center of this is CW Fletcher, who promised Brompton that they could design extrusions and tube shapes that were beyond their wildest dream. And so, the Titanium Brompton represents another chapter in the Brompton story, the creation of an entirely new factory called Brompton Fletcher, based in Rotherham. This bike, called the T-Line, employed 150 new parts, all tooled and produced by Brompton Fletcher. Another step in Brompton Bicycle’s history. Check out the T-Line here.

Oh G, not enough?

By now we hope the reader can understand just how special the Brompton they own or want to buy is. Really, we’ve only scratched the surface. For instance, another great thing about Brompton is that parts tend to be interchangeable from year to year. In a world where engineers explicitly plan a products obsolescence, Brompton engineers a bike that is always repairable and worth repairing.

But, the big news in 2025 is the launch of the new G-Line bike. (Check out the G-Line here). In his book, Will Butler-Adams describes how new models will be required in order to conquer new markets. Markets like the USA are such a challenge. Whereas the original Brompton design was meant for train commuters who rarely left urban London, Brompton users have pushed the original design to long intercity tours (one person even rode around the world!).

The need for an intracity bike that could double as a longer-distance intercity bike was a customer demand that pushed the limits of the original bike. In huge, largely un-urbanized countries like the USA and Canada, where access to nature is always within reach, a bike that could multitask country and commute could be a game-changer. At the time of writing we have Canada’s only G-Line available for test ride, and you definitely need to give it a try!

In October, 2024 we hosted the CEO of Brompton North America. Soon after we did the first launch event for the G-line in Canada. We believe the G-Line promises to revolutionize the folding bike market in Canada. And, since this bike deserves its own article, we’ve written that here.

The Story Continues…

With Pedaal, we can’t wait to see where our long partnership with Brompton takes us. From first importing Brompton back in 2006 to starting Pedaal, we’ve helped make Brompton Bicycle history. And, hope to unfold more possibilities for our customers. In a world where 50% of car-traffic is driving under three miles – a highly cycleable distance! – a Brompton opens a frictionless space for you and your neighbour. Imagine the daily commute as the very best part of your day.

Interested in a Brompton? Drop by, send us an email at info@pedaal.com, or book a virtual or in-store sales appointment.

Check out all of our Brompton models here!