On Saturday, February 1st, Donald Tump levied a 25% tariff on all goods entering the USA from Canada. Ontario’s Premier, Doug Ford, has called it a “bullet aimed straight at the heart of our auto sector.” In response, Doug Ford has promised $22 billion in “shovel ready” projects. This includes $15 billion to widening the Queen Elizabeth Highway (QEW) and $50 million to wiping out Toronto bike lanes. So, while the auto industry could be decimated by Donald Trump’s tariffs, the Ontario taxpayer will subsidize the higher cost of increased automobile use. Maybe a trade war is a good time to ask who our friends are. Bicycles are friends to motorists by helping cut automobile trip times by 35%. And, the best tools for cyclists come from Denmark and the UK: friends with long-term free-trade agreements.

Update Feb 12: we wrote this piece after Trump’s tariffs were announced, but much of the content still holds. In these times, perhaps Canada should work with non-USA trading partners, especially partners who produce solutions that free our cities from urban gridlock. As we argue, there is no reason for an urbanite to resent a suburbanite for driving. Nor vice-versa. Each makes room for the other. So much of gridlock is made of people choosing the wrong tool for the job. Thus, the solution is diverse: it could mean new highways and it could mean more bike lanes. A tools-based approach that maximizes diversity defends against gridlock and makes our cities more competitive.

Update Feb 24: Tariffs are back! Here’s our list of bikes and where they come from – city bikes especially!

Bicyclists are Everyone’s Friend

If you’re familiar with cognitive behavioural therapy, you’ll know how much of it focuses on breaking free from all-or-nothing thinking. In philosophy, this is called “essentialism”—the belief that one solution answers all questions. Taken to an extreme, essentialism can turn into rigid ideology. Doug Ford is not an essentialist. Well, not entirely anyways – as we shall see. While he is investing in freeway expansions, he’s also funding commuter trains and subways, recognizing that Toronto’s economy depends on a variety of transportation options. After all, everyone needs a way to get downtown.

Yet, while Ford acknowledges multiple modes for suburban commuters—cars, trains, and transit—he seems to overlook the transportation needs of people who already live downtown. Urbanites don’t just rely on cars or transit; they also walk, bike, and use micro-mobility. The more they do, the less gridlock there is for everyone. This matters because Toronto has the third-worst traffic congestion in the world. And, this costs an estimated $44 billion in lost productivity each year. The issue isn’t just suburban commuters clogging the roads—it’s urban drivers making short trips. In North America, 52% of car trips are under three miles. If more downtown residents rode a bike, suburban commuters would benefit from clearer roads. The right tool for the right job makes the entire city run smoother. Of course, bike lanes help.

Making Friends with the Math

At Pedaal, we advocate for a tools-based approach guided by real-world data, and the best example comes from the Netherlands. Before dismissing the Netherlands as some “leftie bicycle paradise,” consider this: the Netherlands has the highest rate of both bicycle and car ownership in Europe. Why? Because the Dutch treat transportation like a toolbox, using the right tool for the right job. To measure this, the Dutch segment different travel distances to determine which tool is most efficient. If you’ve ever visited the Netherlands and marvelled at the number of bikes, don’t assume they replace all other forms of transport. They don’t. Research shows that bikes dominate only in trips under 7.5 km. Beyond that, cars quickly take over – but even here, competition is emerging. E-bikes are challenging car trips up to 15 km, offering a sweat-free, faster commute. Beyond 15 km, cars and commuter trains are the undisputed winners. Even in the Netherlands, bikes can’t compete at those distances.

Ignoring this reality is ideological thinking—essentialism at its worst. Indeed, cyclists can be prone to ideology, but Doug Ford, in his own way, falls into the same trap. His road expansions acknowledge the continued role of cars, and his Metrolinx investments recognize transit’s importance. But applying these solutions to trips under 7.5 km, while tearing out bike lanes, ignores the most urgent gap in Toronto’s transportation system. The real problem isn’t whether we need more cars or transit – it’s recognizing where better tools already exist. Citizens downtown are making this choice whether Doug Ford likes it or not. Toronto’s Bike Share – long a metric for new city cycling adoption – has seen an impressive 5.7m trips in 2023.Ripping out bike lanes won’t kill city cycling’s continued growth. The fear is that Doug Ford’s essentialism will kill citizens.

Closer Friends

To better understand Doug Ford’s perspective, we might look at the distance between his Etobicoke neighborhood and the Ontario legislature downtown—about 18 km. This places him firmly in the 15 km+ commuter category, the longest range for a downtown commuter. Perhaps this distance explains his focus. But, the world has shifted since the suburban boom of the 1970s, and one thing Doug Ford can’t deny is the cost value of proximity. Property values today are increasingly tied to how close a home is to work, errands, and leisure activities. This is measured by a “walk score”—the higher the score, the higher the real estate value. Not surprisingly, bike lanes also boost property values.

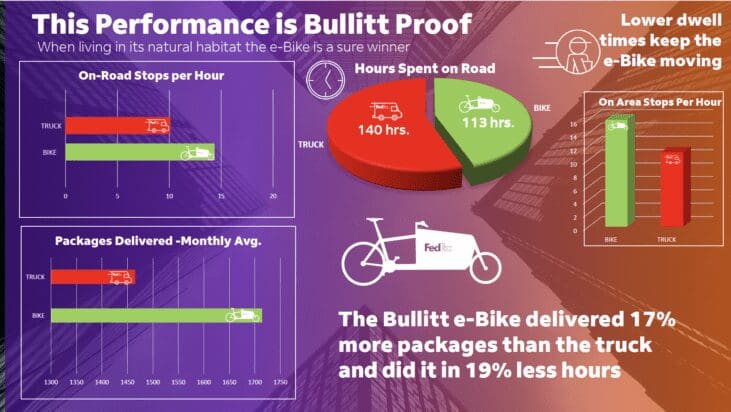

The connection between bike lanes and property value downtown lies in the concept of the “walk score.” As the Dutch model illustrates, this isn’t always about walking. A high walk score means living, working, and playing within a 7.5 km radius. This is what transportation experts call the “last mile.” However, this term is also a misnomer. The “last mile” doesn’t refer to a single mile. It refers to distances that are generally too short to drive and too far to walk. Consider a delivery company like FedEx. Simply put, FedEx cannot afford the cost of the last mile. For companies like FedEx, the last mile is the most expensive part of the journey, consuming up to 53% of the cost, despite its short distance. In 2018, FedEx introduced a test fleet of Bullitt cargo bikes in Toronto. After just a year, each bike delivered 17% more packages daily, in 19% less time, and at a significantly lower cost. For FedEx, this wasn’t a political decision—it was purely about math. In closer distances, bikes are a good friend.

Europe is Canada’s Friend

A tools-based approach to urban cycling also requires a closer look at the tool itself. Take, for example, the best bike for someone navigating the city: is it a mountain bike, a racing bike with narrow tires, or perhaps a balloon-tired beach cruiser? Not quite. The most efficient city bikes often come from places where cycling has been an integral part of daily life for decades. One such place is Copenhagen, a city that, in the 1970s, faced challenges similar to New York—wide, traffic-filled streets, a financially struggling city, and a burgeoning counterculture. Like Toronto, Copenhagen’s bicycle culture was born from a grassroots movement. People simply started choosing to ride. And, as the numbers grew, the government recognized the need to support this shift with better safety and infrastructure.

What makes Danish city bikes and cargo bikes so appealing is how they evolved alongside Copenhagen’s growing cycling infrastructure. Much like North American cities, Copenhagen’s early infrastructure was limited and underdeveloped, which led to bikes being designed with an extra focus on safety. This contrasts with places like the Netherlands, where cycling is integrated into centuries-old, extensive infrastructure. While both countries prioritize safety, Dutch bikes tend to be heavier, while Danish bikes are known for being lighter and more agile in city traffic. This is especially true for Bullitt cargo bikes. This makes them ideal for urban environments where responsiveness and handling are crucial. And with Canada’s free trade agreement with Denmark (CETA), we’ve benefited from steady prices on Danish bikes, even throughout Covid. Our Bullitt and Black Iron Horse cargo bikes, for example, remain as affordable as ever. Certainly cheaper than a car! Thus, a Bullitt offers competitive prices, and a reliable partnership with a friendly trading neighbour. What’s not to love?

The UK is Canada’s Friend

The same is true for Brompton. Pre-covid, a Brompton 6-speed C-Line sold for $2400, and it still does today. That’s because Brompton bikes are made in-house and not by third-party manufacturers in the Far East. While Bullitt might be the best cargo bike out there, Brompton makes not only the best folding bike, but the best city bike too. As we discuss in this blog, a good city bike must be made for the great indoors as much as it is made for the great outdoors. Minimally speaking, a bike that come into your home and work is a bike that will not get stolen. Well, a Brompton solves that problem!

When Brexit happened the UK left the CETA agreement. Nonetheless, the UK and Canada were quick to re-sign a new free-trade agreement called the Canada-United Kingdom Trade Continuity Agreement (Canada-UK TCA). In a world disrupted by Trump’s tariffs, it’s nice to have friends that can offer future oriented solutions. Best thing about a Brompton? It travels easily too. So, if you’re not keen to vacation in the USA, fly with a Brompton or throw it in the trunk of your car for a staycation nearby. Your daily commute and summer vacation all wrapped into one!

Between Friends

Looking at urban transportation require a nuanced approach – one that embraces the competitive role of bicycles in a mobility ecosystem that takes efficiency as its measure. While long commutes may necessitate cars or transit, short trips under 7.5 km are best suited to bicycles. Bicycles offer a faster, more cost-effective option that benefits both urban residents and suburban commuters. By adopting a tools-based approach, cities can create a transportation grid where the right tool is used for the right job. And, with our strong trade relationships with Europe, Canadian consumers can get the right tools for the job – without the inflated prices seen in the post-pandemic market.

We appear to be in a time of great division. However, rather than focusing on division, we may want to recognize the contribution city cyclists make. City cycling, alongside transit, driving and walking make our cities more competitive, efficient and enjoyable. We can’t stop Donald Trump and his tariffs. But, living well is the best retribution. And, if you live downtown, living well is best on a bike.

Stay in the Know. Join our Newsletter!