In firefighting, a fire line is a controlled boundary set to prevent the spread of a wildfire. It’s a strip of land where vegetation is cleared away to stop flames from advancing. We might employ this metaphor for today’s bicycle industry. Here, the fire line as the legal boundary that unsafe e-bikes should never cross. That’s because unregulated e-bikes are catching fire, literally. Regulation has not kept up, safe products are given the same status as unsafe products, and legislators are without a hose. Luckily, proper e-bikes do exist. These bikes not only light a fire under legislators butts, but they will totally set you on fire too. Safe, shorter commutes and a smile on your face. That’s the way you fight fire with fire!

A House Divided, a House on Fire

Unsafe e-bikes are making headlines these days. In January 2024, a fire broke out on a Toronto TTC subway due to an electric bike battery. Described as “significant and aggressive,” the blaze ignited within seconds. In November 2024, the TTC temporarily banned all e-bikes while investigating new safety standards. The same pattern is unfolding globally in places where regulation lags. London experiences an average of six house fires per week linked to e-bike batteries, and in New York City, 200 fires occurred in 2022 alone.

If e-bikes can set literal houses on fire, the bike industry itself is a house divided. On one side, mainstream stores sell safe, highly regulated e-bikes and work with legislators to improve safety through controlled power-to-weight ratios, firmware that enforces speed limits, and strict battery standards. On the other side is a parallel market of direct-to-consumer (DTC) vendors who exploit legal loopholes by selling motorized vehicles disguised as bicycles. While one side prioritizes safety, the other actively undermines it. If you have a feeling this is happening in Canada, it most certainly is.

Decoy Pedals

The first instance of this problem might be traced to the Netherlands. In the early 1960s, the Netherlands saw an influx of “Bromfietsen”—two-stroke gasoline mopeds equipped with pedals. Were these pedals there to propel the bike? No, they were there to evade motor vehicle regulations. According to regulation at the time, a bike was something that had pedals. Thus, as long as the Bromfietsen had pedals – and that they marginally worked – it was a bicycle. Ontario legislation also states that an e-bike must have “working pedals.” Despite this, it doesn’t state the pedals ever have to be used. It’s the same trick in a different place, decades later. Only, the Bromfietsen never caught on fire. The stakes are higher.

Initially, lawmakers in the Netherlands were unprepared. But, as these vehicles flooded bike lanes and caused countless accidents, legislation had to catch up. The government responded with mandatory third-party insurance (1965), insurance plates (1966), helmet laws (1975), and ultimately banning Bromfietsen from bike lanes (1991). Legislation doesn’t happen, in other words, overnight. Today, Dutch law draws a clear distinction: if the pedals do not always propel the bike, it is immediately and with all effect a motor vehicle, full stop. A motor can assist pedalling, but it cannot replace pedalling.

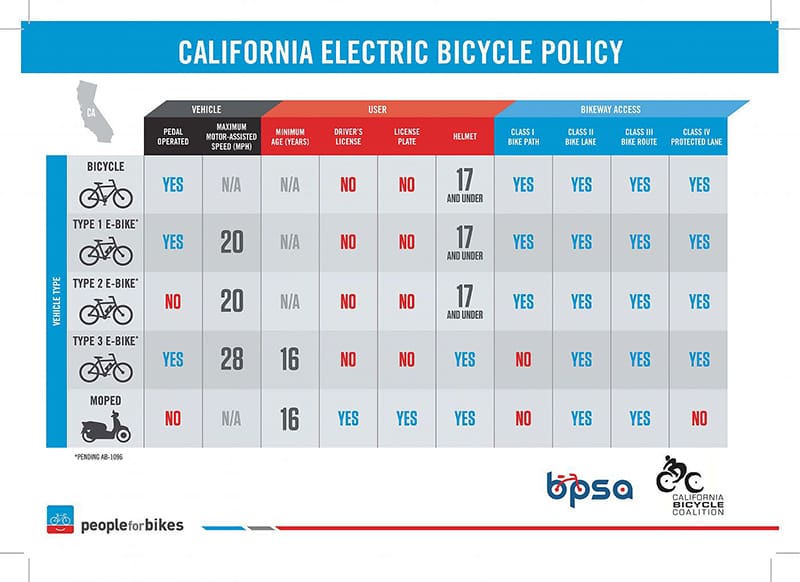

Pedals, Fire & Risk

Today’s e-bike version of the Bromfietsen is even more dangerous. These electric variants don’t just exploit regulatory loopholes; they are a literal house on fire. In the USA, PeopleForBikes calls these electric Bromfietsen “Class-2” e-bikes. These are electric bikes with pedals that are more legal ornamentation than anything else. In the USA, Class-2 e-bikes currently enjoy all the same rights as a regular bicycle. Dutch legislators might clench their fists at this, but they would also agree that legislation must start by cataloging differences. If, one day, Class-2 e-bikes are reclassified as motor vehicles – as they were in the Netherlands – it will be because they have proven to be fundamentally different from Class-1 pedelecs. The unpleasant thing is that this difference is usually revealed through injuries and fatalities.

Unfortunately, most of Canada lacks any sort of e-bike class system. This means a European pedelec with fireproof EN-certified batteries and a controlled pedal-assist system is treated the same as a throttle-powered bike with an explosion-ready battery. This means that as accidents pile up, lawmakers have no way to determine which type of e-bike is responsible.

Power without Pedalling

Looking back to the Bromfietsen, we can witness two historical approaches to safety. Class-2 bikes generally originate from China and thrive in loosely regulated markets. Class-1 pedelecs originate in Europe and were developed under the safety regulations that emerged in direct response to the Bromfietsen problem. On a Class-1 e-bike, the rider cannot access the peak power of the motor unless the conditions demand it. On a Class-1 system, the rider only has access to the motors peak power when certain conditions obtain – whether that’s big hills, heavy loads, gale force wind, or all of the above. But, to access any power at all, the rider must be always be pedalling.

On Class-2 bikes, the rider has access to the motors peak power whenever they want. And, when you consider the 120kg allowable weight given to an e-bike under Ontario regulations, the power-to-weight ratio can equal that of a Vespa Motor Scooter! That’s why Dutch law requires insurance and licensing for these vehicles. Not only are they more likely to cause accidents but the accidents are more likely to be serious.

The New Bromfietsen Battle

But, even a mature legislative ecosystem like the Netherlands continues to play whack-a-mole. The grey illegality of the Bromfietsen, it seems, continues to live on. The latest trend in the Netherlands is the so-called fatbike – a bike that looks like many of the food delivery bikes you would see in Toronto. In the Netherlands, these bikes are sold as Class-1 pedelecs, but they are also sold with easily hackable firmware to increase speed and throttle kits that consumers can install themselves. This is pure cynicism.

Under Dutch law, the moment a bike gains a throttle, it is legally a motor vehicle. However, because these fatbikes are not sold as motor vehicles, they are able to leave stores without insurance, plates, or helmet requirements. And so, enforcement becomes that game of whack-a-mole. Officers have no way to verify firmware modifications or spot-check hidden throttles. And so, Dutch legislators are working on stronger manufacturer-side compliance, requiring firmware that cannot be altered and systems that reject throttle installations. But, unlike places like Ontario, lawmakers have the literacy to enforce regulations at the consumer, retailer, and manufacturer level. It couldn’t be more different here in Canada.

The Bicycle Industries Blind Spot

And so, we’ve seen how the battle between Class-1 and Class-2 highlight two competing philosophies around safety. But the problem isn’t just lagging legislation – it’s the mainstream bicycle industry itself.

Walk into almost any bike shop in downtown Toronto, and you’ll see an industry that has largely ignored the rise of urban cycling. The modern bike shop caters to performance-oriented hobbyists, not city commuters or food couriers. Historically, bicycles thrived when people lived, worked, and socialized downtown. But as suburban sprawl stretched daily commutes, the bicycle couldn’t compete with automobiles. The bicycle transitioned from a tool of transportation – once central to women’s emancipation – to a recreational pursuit, increasingly marketed toward men. Walk into a bike store and you can feel that little has changed since then.

This cultural problem remains a serious bottleneck for the growth of city cycling. Luckily, there is the internet. As online shopping grows, bike shops are bypassed, but so are regulations and quality standards that us bike stores hold so dear. That’s why stores like Pedaal exist, to break the bottleneck in the bike industry with literacy around city cycling and legislation. And, to work with legislators themselves on best practices. Like any mainstream bike store, all of our bikes are highly regulated Class-1 electrical assists. But, unlike most mainstream bike stores, our bikes are commuter tools designed for better city cycling.

Class-2 E-Bikes: A Fire Hazard Ignored

Like the Bromfietsen, today’s Class-2 e-bike craze is a matter of bike lane safety, but more critically, fire safety. A well-designed battery relies on high-quality cells for stable voltage and temperature and a strong Battery Management Systems to regulate charging and prevent overheating. When manufacturers cut costs with inferior components, the risk of thermal runaway skyrockets, leading to catastrophic fires. Frequent charging cycles and road vibrations only increase the danger, making stringent battery standards essential. A great article about batteries can be found here.

Health Canada has acknowledged the risks of lithium-ion batteries, adding them to its General Prohibitions List in July 2024 as “hazards of concern.” This suggests future regulatory action. But unlike Europe, where EN safety standards are mandatory, Ontario has no such regulations. Worse, it makes no distinction between safe Class-1 pedelecs and hazardous Class-2 imports.

The Safety Gap

The closest equivalent to EN standards in North America is UL certification, a voluntary U.S. safety standard run by a Underwiters Laboratories (UL), a private company. This is a far cry from mandatory certification. While New York City has mandated UL 2849 certification to combat battery fires, Canada has no such requirement.

Regulation comes before enforcement. In 2023, Dutch authorities seized 16,500 fatbikes that failed EN safety standards. These bikes weren’t modified post-sale – they were sold with dangerous batteries. Without enforcement, battery failures will continue to escalate. Ontario faces the same risks, with no mandatory lithium-ion safety regulations and no distinction between pedelecs and bikes where pedals are pure legal ornamentation.

Building Gaps: The Fire Line

The fire lines in the e-bike industry are clear: on one side, we have regulated pedelecs prioritizing safety. On the other, motorized vehicles masquerading as bicycles, skirting regulations, and endangering lives. In the bike lane, its a problem of increased accidents. And, in homes, workplaces and transit it’s a matter of fires. In the bicycle industry, it’s a shadow side and a mainstream side setting the best practices for safety. The fire line, in other words, is pretty clear – even if regulators don’t see it. Speaking of fires, we hope this helps lights a fire under regulators butts!