If you’ve ever taken a logic course, you’ve encountered Aristotle’s distinction between genus and species. Genus is the broad category—like rock music—while species is a more specific subset, such as punk rock. Everything in the species belongs to the genus, but not everything in the genus belongs to the species. Classic rock, for instance, is part of rock but not punk rock. The key to classification is identifying specific difference. Legislators, however, seem to struggle with this concept when it comes to electric bikes. They can’t tell jazz from rock, or worse, yacht rock from heavy metal. The result? Our bike lanes are drowning in heavy metal – literally. Ontario’s e-bike legislation lumps together vastly different machines, failing to recognize that some are much closer to motorcycles than bicycles. And when you mix grannies, kids, and 120kg electric mopeds in the same lane, you don’t get harmony – you get a mosh pit.

A Cultural Shift on Two Wheels

The root of the problem is cultural. Urban infrastructure and legislation were shaped in an era when the car was king. As Richard Florida has pointed out, cultural values can be mapped onto property values. In the 1970s, urban centers suffered from pollution, crime, and the dominance of cars, causing property values to drop. Meanwhile, suburban homes—with their ample driveways and two-car garages—were worth more. The bicycle, ideal for trips under 7.5 km, simply couldn’t compete. It was either an unused relic from Canadian Tire collecting dust in the garage or an expensive hobby for those who preferred cycling to golf, racquetball, or axe throwing. In short, cycling was sidelined.

Then came the late ’90s, when magazines like Wallpaper began glorifying urban life. Property values shifted, and suddenly, proximity to cafes, neighbors, and work became a new measure of success. Walking and cycling weren’t just practical; they were aspirational. The car, once a symbol of freedom, started looking like an expensive burden. But while our culture changed, our legislation didn’t. Lawmakers still seem to think of bikes as dusty garage toys, failing to account for the fact that bicycles—and now e-bikes—are essential urban transportation. This legislative blind spot has allowed Ontario’s bike lanes to be overrun with what can only be described as heavy metal on wheels.

Ontario’s E-Bike Laws: A Power Ballad Gone Wrong

Under Ontario’s e-bike legislation, an e-bike can weigh up to 120kg, must have “working pedals,” and can have a motor of up to 500W nominal power. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands – where bikes are treated as real transportation – e-bikes are limited to 250W, must be pedal-assist only, and cannot exceed 55kg. The result? Ontario allows enormous, powerful machines in bike lanes designed for, well, bicycles. And, that’s dangerous.

If we’re looking for specific difference, let’s start with “working pedals.” In Ontario, e-bike pedals need only (a) be present and (b) be technically functional. Whether you actually use them is irrelevant. This quirk originates from the Bromfietsen craze of the 1970s—a European and North American fad for gas-powered mopeds with pedals. These bikes emerged in the 60’s and 70’s, when the Netherlands was flirting with the automobile and bicycle sales were falling. Because these machines had “working pedals,” (sound familiar?) they were, at first, legally considered bicycles. But in the bike lane they were fast, heavy, and dangerous. After too many fatalities (cue the death metal), European lawmakers cracked down, classifying them as motor vehicles. The moment that happened, sales plummeted.

Sound familiar? Today, Ontario’s streets are filled with e-mopeds and throttle-powered e-bikes that technically have pedals but are rarely used. Some of these machines have pedals so small and awkward that their “workability” is a joke. And as long as that question remains unanswered—what exactly counts as “workable”?—the heaviest and most powerful bikes will continue to populate the bike lane.

Enter the Pedelec: Math Rock Meets the Bicycle

Europe’s solution to the Bromfietsen debacle was the pedelec, a truly pedal-operated e-bike. Unlike throttle-assisted e-bikes, pedelecs by necessity require you to pedal for the motor to engage. More importantly, the motor only provides power in proportion to the effort you put in. No pedaling? No power. This is why pedelecs are still bicycles and not motor vehicles.

Pedelecs work through a system that senses wheel speed, pedal cadence, and torque. If you’re climbing a hill, the system notices the slowdown and provides more power. Once you crest the hill, it dials back the assistance. The result is a smooth, intuitive ride—like math rock for bicycles, precise and harmonious. Compare this to a throttle-assisted e-moped, where the motor doesn’t care if you’re pedaling or not. On a throttle-assisted moped, you have the ability to access the systems peak power with the press of a button. On a pedelec, peak power can only achieved if the conditions require it. That actually makes a pedelec more fun. It’s kind of reading your mind! What do they look like? We happen to sell the best cargo bike and folding bike pedelec on the market. Check them out!

Power-to-Weight Ratios: Ontario’s Heavy Metal Problem

European legislators understand that bike lane safety isn’t just about speed limits—it’s about power-to-weight ratios. In the Netherlands, e-bikes and cargo bikes over 75kg have strict power limits: e-kick scooters max out at 400W peak power, while heavy-duty cargo bikes are capped at 1250W peak.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, e-bikes can have 500W nominal power but often reach 3000W peak power. Combined with a max weight of 120kg, some Ontario “e-bikes” have power-to-weight ratios (PWR) approaching those of small motorcycles. Consider the following power-to-weight ratios:

- Smart EQ Car: 32.3W/kg

- 50cc Vespa: 19W/kg

- Ontario ebike legislation for max power and weight (120kg, 3000W peak power): 25W/kg

- Typical Food Delivery bike in Toronto (30kg, 1000W peak power): 33.3W/kg

- Lightweight EU bike pedelec (25kg, 500W peak power): 18W/kg

- Heavy EU cargo bike pedelec (55kg, 750W peak power): 13W/kg

While Ontario’s e-bike legislation recognizes that a 120kg bike may require more power to get moving, the rules also permit lighter-weight bikes with far too much unregulated power. This helps explain the disruption that food delivery riders present. These riders ride throttle-assisted bikes, are rarely seen pedalling, and can access the peak power of their motors with the press of a button. If this seems reckless, it doesn’t help that their employers reward recklessness. No wonder it feels like a metal concert out there.

Speed Metal and Power Metal. Turning down the Amp.

But power-to-weight ratios in the Netherlands aren’t just about limiting high-powered machines—they’re about ensuring that all bikes in the lane behave predictably. Dutch legislators cap power output relative to weight for two key reasons:

- Syncing Acceleration with Bicycle Traffic: A heavy cargo bike needs more power to accelerate at the same rate as a standard bicycle. Without that boost, it would lag behind at intersections, disrupting the flow of bike lane traffic. By regulating PWR, Dutch law ensures that even with additional weight, electric bikes still move like regular bikes.

- Preventing Excessive Power in Lightweight Vehicles: A 25kg e-kick scooter with a 2000W peak motor would accelerate like a rocket, creating massive speed differentials within the bike lane. Instead, Dutch law ensures that smaller, lighter vehicles get proportionally less power, keeping acceleration smooth and predictable.

This all ties into the core Dutch philosophy of bike lane safety: physical separation from cars is only part of the equation. Just as important is ensuring that all vehicles in the lane travel at roughly the same speed. In Ontario, it’s common to see an e-moped blasting through at 50 km/h while a regular cyclist cruises along at 15 km/h. That’s a recipe for crashes. In the Netherlands, acceleration and top speed are tightly controlled, because on a pedelec, power is delivered via pedal input, not a throttle. Ontario’s e-bike legislation treats e-bikes like mopeds from the 1970s. As long as they have “working pedals,” the heaviest, most overpowered bikes are permitted in the bike lane.

Legislation Done Right: The Dutch and US Models

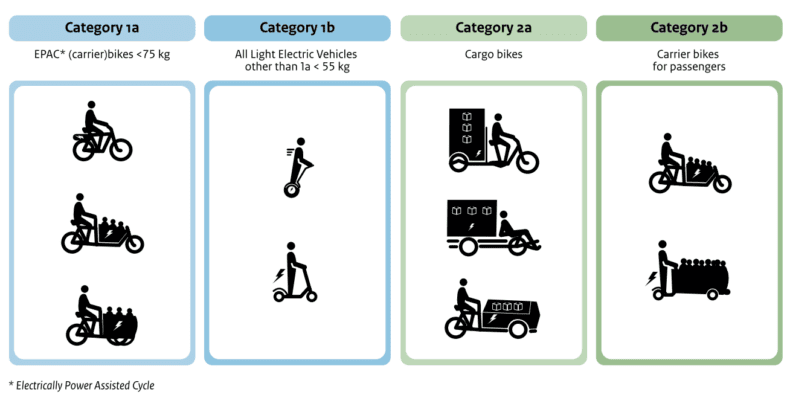

But, let’s revisit Aristotle and his logic of genus and species. The Netherlands classifies all small electric vehicles as Light Electric Vehicles (LEVs), using LEV as the genus rather than “bicycle.” This creates space for better legislation around kick scooters, heavy-duty cargo bikes, and new vehicle categories that the U.S. system tends to ignore. Their classification system:

- Pedelecs (1a): Computer-assisted, pedal-powered e-bikes. No insurance, registration, helmet or license required.

- E-kick scooters (1b): Require insurance due to throttle control.

- Heavy cargo bikes (2a, 2b): Throttle-allowed, but require a license and insurance. (See here for an excellent run-down of the categories)

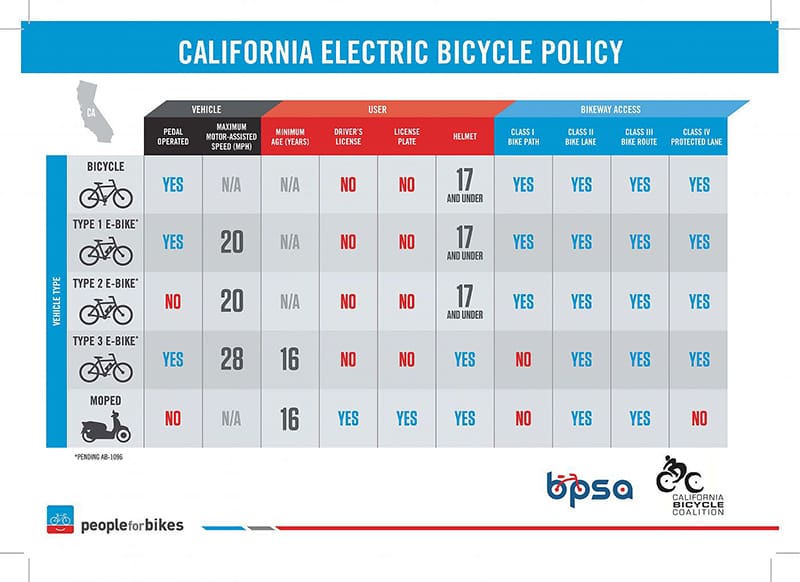

The U.S. “People for Bikes” system splits e-bikes into three classes. A Class-1 is a pedelec bike that is “pedal operated.” A Class-2 bike has pedals but isn’t necessarily pedal-operated. The latter bikes are the dominant machine used by food-delivery riders who rarely pedal them. As we saw with the Bromfietsen rage in Holland, once the bikes are on the streets, legislators can only deal with them by categorizing them first. In Holland the Bromfietsen ended up being legislated as a species of motor vehicles. People For Bikes already includes Class-2 under the genus of “Bicycle.”

If there’s a dirty little secret to these throttle-assisted bikes, it’s that if you remove the throttle most Class-2 bikes are pedelecs underneath. In fact, in Holland these bikes are actually sold as Class-1 bikes with throttle kits that the consumer can easily install. Once a bike has a throttle it is by definition an e-Moped and requires insurance and a license plate. But, because it wasn’t sold as an e-Moped it ducks under the rules. This causes a legislative game of whack-a-mole, especially since these bikes have caused innumerable accidents. Good legislation at least makes sure the moles don’t take over.

Baselines: Turn up the Bass!

As the Dutch LEV model shows, if regular bikes and pedelecs form the baseline for a homogeneity of power and speed in the bike lane, then this informs safety measures for other LEV’s. We have no issue with scooters or heavier cargo bikes that have throttles, so long as power is regulated based on weight to achieve this homogeneity. What disrupts this homogeneity is Class-2 food-delivery bikes and their unregulated power-to-weight ratios.

This limited approach might also explain why the People for Bikes definitions make no room for heavier-duty cargo bikes and smaller micro-mobility devices. Heavier bikes—such as those over 75kg—are excluded from the People for Bikes classification system. Likewise, smaller micro-mobility devices aren’t even on the chart. This is why we ultimately prefer the Dutch approach. By beginning with the genus of LEV, more diversity can be recognized and legislated – including the possibility that Class-2 bikes remain, but are further regulated to reduce recklessness. Thanks, Aristotle!

Piloting New Legislation

This brings us to Ontario’s 2021 Cargo Bike Pilot, which – surprise! – aligns much more closely with the Dutch LEV model. The pilot was launched to address the growing issue of commercial last-mile delivery, which is gridlocked and inefficient, especially with traditional vehicle traffic. The idea was to push for an alternative to reduce congestion, enhance shipping efficiency, and drive down costs—all while embracing cargo bikes that can handle these commercial needs.

Ontario’s decision to experiment with this kind of solution marks a rare moment of harmony with European electric vehicle trends, recognizing the potential for cargo bikes in urban logistics. However, Ontario still makes the critical error of conflating pedelec bikes with throttle-controlled bikes, a misstep that continues to muddy the legal landscape and stifle the classification necessary to separate the two.

Conclusion: Turning Down the Volume

Ontario’s e-bikes legislation is, as we said, a bit of a mosh pit. There are other problems with it too. By failing to recognize the specific difference between pedelecs and throttle-assisted e-bikes, legislators have filled bike lanes with high-powered, heavy vehicles that behave more like motorcycles. The Dutch learned this lesson decades ago. The U.S. is at least trying. Ontario? Still headbanging to the same old track. If we want safer, more functional bike lanes, we need to move away from the outdated “working pedals” rule and adopt a clear a pedelec standard. We believe this will increase micro-mobility traffic, reduce automobile gridlock, and make cities like Toronto more competitive and healthy. Especially in these crazy times.